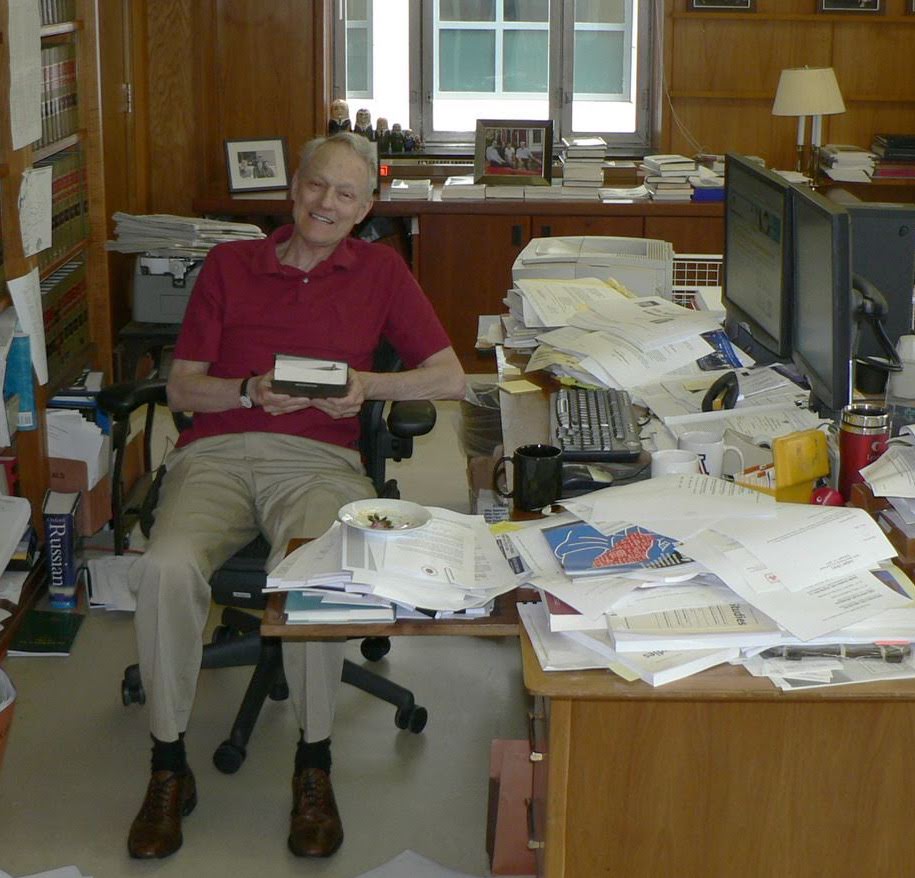

Yesterday, one of America’s greatest legal minds, Judge Stephen F. Williams for whom I had the honour to clerk in 2007 passed away because of COVID-19. A graduate of Yale and Harvard Law School with family roots going back to British settlers who arrived in America on the Mayflower, I knew him as a modest person and an exemplary intellectual who made a significant impact on American law.

Appointed by President Ronald Reagan to the Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit in 1986 Judge Williams has been one of the longest-serving judges on the court. The so-called DC Circuit located just across the road from the Capitol is regarded as the most important court in the United States after the Supreme Court. It has jurisdiction over many disputes arising in the District of Columbia, which hosts the most important American political institutions and federal agencies. According to the Washington Post, Judge Williams heard cases until earlier this year.

Open-minded, intellectually curious, hardworking, polite and solicitous to everyone around him, Judge Williams served as an example for those who were lucky to regard him as a mentor.

Meeting Judge Williams

We first met with Judge Williams in April 2001 when the US Consulate in St Petersburg organised a trip for the Russian team participating in the final rounds of the Philip Jessup Moot Court Competition to the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit. At that time I was a student at St Petersburg curious about foreign legal systems and had no idea about the role of this court. Since our first meeting with the judge, we kept in touch — I would send him a Christmas card with a few words in Russian and he would occasionally email me asking a question related to Russian history or language.

Five years after our first meeting I have been admitted to Harvard Law School from which the judge himself graduated magna cum laude in 1961. The judge congratulated me and suggested to approach Professor Christine Jolls to see whether she would need a research assistant. Unfortunately, Professor Jolls was moving to Yale Law School in the next academic year. However, she kindly recommended me to get in touch with Professor Reiner Kraakman, who then accepted me for a research assistant position. As a result of this hint and indirect introduction from the judge, I could not only study but also work part-time at Harvard Law School, which not many LLM students did.

After a few months in the United States, I vaguely understood that working for a federal judge was considered a highly desired career path. When we studied Judge Williams’ pronouncements on various administrative law issues in Mark Tushnet‘s Regulatory and Administrative State class, I became even more interested. I approached Judge Williams to explore whether I could work as a law clerk in his chambers. He quickly responded that he would be happy to see me at his chambers as an ‘extern’ law clerk.

Essentially, that meant that I would do similar work as ‘regular’ clerks but would not be paid. I did not have a JD degree from a US university, which was a prerequisite for a full year clerkship position. I was happy to accept it, particularly because in 2008, the world economy went through a serious financial crisis. Finding a job then was extremely difficult, particularly for someone with a Belarusian passport, educated in a civil law jurisdiction and not speaking English as a native language.

Working with Judge Williams

In August 2007, I moved from Cambridge, MA to Washington, DC to work in the chambers of Judge Williams. When I arrived, they had several pending Guantanamo cases and recently rendered a judgement in the massive Microsoft antitrust case – United States v. Microsoft Corporation case. This court serves a springboard for many future judges of the US Supreme Court, including Brett Kavanaugh whom I also had a chance to meet. Justices of the US Supreme Court would also visit to give talks to the clerks and judges.

When I was looking for accommodation in the DC area, I asked the judge for advice on how to distinguish between good and bad neighbourhoods. He thought for a moment and recommended to see whether there were people in the streets sitting and doing nothing. He was certainly not that type of person. He kept himself very busy with his court cases, academic writings and devoting time to his five children, many grandchildren, friends and colleagues. At the same time, he would also find time to review a paper in progress or meet for lunch with a former clerk and generously shared his time and ideas with others.

I had a privilege to work with Judge Williams on several cases, which involved the application of international law in federal proceedings. I conducted research and then discussed draft memos with the judge, who would then question the arguments made and the sources, directing me on how to improve it. I remember some cases involved creditors trying to get hold of the property of foreign embassies located in Washington, DC, but the most interesting case was Agudas Chasidei Chabad v. Russian Federation (D.C.Cir.2008).

The Chabad case was a real treasure for a young law clerk interested in international law. It involved sovereign immunity, customary international law, state succession and history. That case involved nationalization of property looted during the Second World War. In that case, the Lubavitch Chasidim or Chabad Chasidim (Chabad), a Jewish religious entity, sought to reclaim a collection of sacred books and manuscripts held by the Russian Federation. This litigation raised many controversial legal issues of historical disputes against a foreign sovereign in national courts.

Following the initial chat about the case, the judge even allowed me to draft a section of the Chabad judgement dealing with customary international law, which he has subsequently revised and finalised. As was the custom in his chambers, when I delivered a draft of my section I accompanied it by a cart from the court library with all cited cases and materials. The judge would meticulously read each source before making his edits.

Working in his chambers gave me a chance to meet some of the brightest young American lawyers of our generation. Following my clerkship, I had a pleasure to join reunions of clerks hosted at the modest house of Judge Williams on Columbia Street N.W. The crowd of his former clerks included interesting personalities — from Professor Eric Posner of the University of Chicago to Jonathan Soros, son of George Soros. No doubt the judge contributed to shaping the world view of many influential Americans.

Judge Williams and the pre-revolutionary Russia

As a self-admitted ‘Cold War baby’ Judge Williams developed an interest in the pre-revolutionary period of Russia to be able to better predict what will happen to Russia next. In the years I know him, he actively engaged in Russia-US judicial cooperation activities. Because I did my first degree in Russia, I was a natural liaison or Russia-related activities, including accompanying Chief Justice John Roberts on some of those activities.

The picture below shows Judge Williams to the left of Anton Ivanov, who was then the Chairman of the Supreme Arbitrazh Court of Russia.

The judge’s interest in pre-revolutionary Russia was perhaps the main reason why we initially met and corresponded for almost two decades. In 2006, his book Liberal Reform in an Illiberal Regime: The Creation of Private Property in Russia, 1906-1915 was launched at the American Enterprise Institute and the former Prime Minister of Russia Yegor Gaidar who was on the panel spoke highly of the book. The book was about Pyotr Stolypin, another Russian Prime Minister who initiated major agrarian reforms granting private land ownership to the peasantry and assassinated in 1911.

When I worked for the judge between August and December 2007, he was busy with a biography of Vasily Maklakov, a Russian lawyer and statesman who sought liberal reform and a rapid evolution towards a constitutional monarch. Judge Williams would spend days working in the Library of Congress and speaking to historians, librarians and archivists. He even travelled to Moscow to work in state archives there. His book titled The Reformer: How One Liberal Fought to Preempt the Russian Revolution was published three years ago and is highly recommended not only to those interested in Russian history.

This 2018 Harvard Law School book talk about Vasily Maklakov introduced by his former clerk Jonathan Zittrain is perhaps one of the last publically available videos of the judge.

The central question of his last two books was whether reforms towards liberal democracy and prosperity could take place as a voluntary decision of autocrats, rather than as a response to pressure from disenfranchised groups. Today this question is relevant for Russia and Belarus more than ever. Judge Williams showed using fascinating historical evidence that without civil society, the formal institutions supporting the rule of law were quite inadequate.

In his daily life, Judge Williams took care of himself but has been very aesthetic. He lived in a not-so-posh neighbourhood of Washington, DC and has even been mugged there once. However, he preferred that simple neighbourhood and commuted by bike to his chambers. After I heard that the judge’s travelled with his father (then in his late 80s) to St Petersburg, I was sure the judge would live well into his 90s. However, he passed away at the age of 83.

Judge Williams left an impressive intellectual legacy, sadness and warm feelings in the hearts of those who knew him.

Yarik Kryvoi

British Institute of International and Comparative Law